What Is News?

How Americans decide what ‘news’ means to them – and how it fits into their lives in the digital era

Measuring people’s news habits and attitudes has long been a key part of Pew Research Center’s efforts to understand American society. Our surveys regularly ask Americans how closely they are following the news, where they get their news and how much they trust the news they see.

But as people are exposed to more information from more sources than ever before and lines blur between entertainment, commentary and other types of content, these questions are not as straightforward as they once were. This unique study from the Pew-Knight Initiative explores the question: What is “news” to Americans – and what isn’t?

The Pew-Knight Initiative supports new research on how Americans absorb civic information, form beliefs and identities, and engage in their communities.

Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. Knight Foundation is a social investor committed to supporting informed and engaged communities. Learn more >

Before the rise of digital and social media, researchers had long approached the question of what news is from the journalist perspective. Ideas of news were often tied to the institution of journalism, and journalists defined news and determined what was newsworthy. “News” was considered information produced and packaged within news organizations for a passive audience, with emphasis (particularly in the United States) placed on a particular tone, a set of values and the idea of journalism playing a civic role in promoting an informed public.

“I think there’s been this huge democratization where the institutions have lost the power they had to control what people saw and watched.”

–Ben Smith, editor-in-chief, Semafor

In the digital age, researchers – including Pew Research Center – increasingly study news from the audience perspective, what some have deemed an “audience turn.” Using this approach, the concept of news is not necessarily tied to professional journalism, and audiences, rather than journalists, determine what is news.

The results of this study capture these changing dynamics of news consumption in the U.S. The journalists and editors we interviewed agree that in the digital age, the power to define news has largely shifted from media gatekeepers to the general public. And discussions with everyday Americans confirm the idea that its definition varies greatly from person to person, with each bringing their own mindset and approach to navigating a dizzying information environment.

These perceptions are consequential because news – regardless of what people consider it to be – remains a consistent part of most Americans’ lives today. About three-quarters of U.S. adults (77%) say they follow the news at least some of the time, and 44% say they intentionally seek out news extremely often or often. This study provides a deeper understanding of what “news” means to Americans and how they decide where to turn for it.

Key findings:

- Defining news has become a personal, and personalized, experience. People decide what news means to them and which sources they turn to based on a variety of factors, including their own identities and interests.

- Most people agree that information must be factual, up to date and important to society to be considered news. Personal importance or relevance also came up often, both in participants’ own words and in their actual behaviors.

- “Hard news” stories about politics and war continue to be what people most clearly think of as news. U.S. adults are most likely to say election updates (66%) and information about the war in Gaza (62%) are “definitely news.”

- There are also consistent views on what news is not. People make clear distinctions between news versus entertainment and news versus opinion.

- At the same time, views of news as not being “biased” or “opinionated” can conflict with people’s actual behaviors and preferences. For instance, 55% of Americans believe it’s at least somewhat important that their news sources share their political views.

- People don’t always like news, but they say they need it: While many express negative emotions surrounding news (such as anger or sadness), they also say it helps them feel informed or feel that they “need” to keep up with it.

- People’s emotions about news are at times tied to broader feelings of media distrust, or specific events going on at that time – perhaps in combination with individuals’ political identities. For instance, partisans often react positively to news about their own political parties or candidates and negatively to news covering their opposition, which means feelings can shift with political changes.

The answers to the question “What is news?” are not always straightforward. As this study confirms, the definitions people hold for news may not be consistent with their actual behaviors. There are sometimes clashes between what people believe others think of as news and what “feels” like news to them. And people often categorize information as “news” along a continuum rather than as a simple yes-or-no question. Those perceptions vary depending on the platform, source and individual.

To better understand the nuances of defining “news,” this multimethod project draws upon three key sources of data:

- A qualitative online discussion board – where participants (57 U.S. adults) privately completed a range of activities, including open-ended questions, canvas illustrations, rating exercises, and video and screen recordings

- A nationally representative survey of 9,482 U.S. adults

- On-the-record, in-depth interviews with 13 journalists and editors

Discussion board and interview responses were lightly edited for spelling, punctuation and clarity. For more details on each of these approaches, refer to the methodology or the key takeaways in our accompanying Decoded blog post.

What Americans think news is – and is not

There is not a one-size-fits-all answer to what “news” is – news means something different to everyone. Some online discussion board participants seemed aware of this: As one man in his 60s said, “What I consider news might not be news to others.”

Several attributes of the information itself – including its topic and source – as well as participants’ own identities and attitudes play a role in how people (knowingly or not) determine whether something counts as news to them. And in many cases, asking people to describe what news means to them seems to result in answers about what they believe makes for high-quality news.

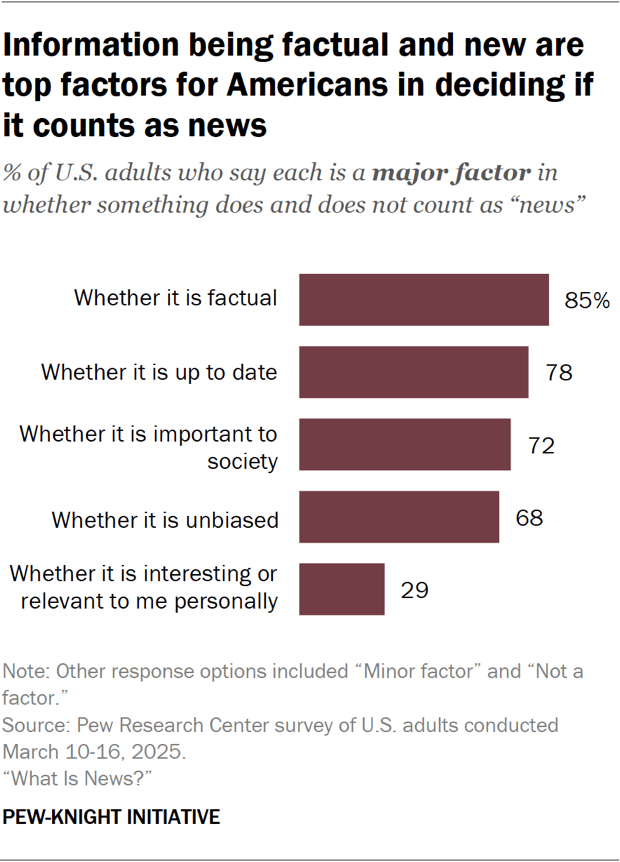

In both our qualitative and survey research, three attributes remain consistent when people describe what news means to them: Information must be factual, up to date and important to society to be considered news.

“I think that has actually been quite scary for all of us because you have people who have become willing to believe things that are demonstrably not true. … If they’re willing to believe that … how do you get them to read and process legitimate news?”

–Tracy Weber, managing editor, ProPublica

The factual nature of information is a key factor in how Americans determine whether something is news or not. In our online discussion board, participants widely said they want news to be “just the facts,” not opinions or commentary.

However, journalists expressed concerns about media literacy among the public, including the audience’s ability to discern between “what is actual news and factual” versus “unverified sources” and false information.

For many, news also includes anything that is “new” or up to date, regardless of its impact or relevance. As one woman in her 50s put it, “News to me is the latest events in the world, both bad and good, as well as the sporting and business world happenings.”

These perceptions also emerge in our survey data: U.S. adults are most likely to say that whether something is factual (85%) or whether it is up to date (78%) are major factors in thinking about whether it counts as news.

These are followed by whether the information is important to society, with 72% of respondents considering this a major factor in deciding what’s news. In the online discussion board, the idea of “importance” came up in two ways:

- News is societally important: The information is related to current political and civic issues that they feel hold significance to society or that affect people. One woman in her 20s defined news as “information that affects people on a larger scale and globally.”

- News is personally important: The information interests them, is relevant to them or affects their personal lives. As one man in his 20s put it: “News is the information that matters to me and affects my life on a consistent basis.”

“The definition of what is news is blurring. … News is a combination of what you need to know and what you want to know and what you find intriguing and didn’t necessarily know you wanted to know about.”

–David Folkenflik, media correspondent, NPR News

Americans are significantly less likely to say personal relevance is a major factor (29%) when they think about what counts as news. But personal importance or relevance came up often when online discussion board participants defined news in their own words – and especially when they actually encountered information online.

People also hold consistent ideas about what is not news:

Opinion or commentary is not news. Both journalists and participants make clear distinctions between factual reporting and personal opinion, further emphasizing an idea of news as “just the facts.” The word “hearsay” came up a few times to refer, in participants’ eyes, to information that includes opinions or comes from nontraditional sources (e.g., friends, YouTubers).

“[News is] based in fact and it’s reported. It’s not somebody’s opinion or interpretation of an event or an incident.”

–Kimi Yoshino, editor-in-chief, The Baltimore Banner

Journalists referred to high-quality news in the same way that participants defined news: “factual” reporting without inserted opinion and with attributed sources.

Similarly, Americans say news should not be biased. Political bias was a recurring – almost universal – concern among participants. Many said they believe that at least some bias from news sources is inherent and unavoidable. This creates an underlying current of cynicism regarding whether anyone can completely trust any news source, something journalists have perceived in their audiences as well.

Participants’ ideas of news as not being “biased” or “opinionated” at times conflicts with their actual behaviors – for instance, they might regularly consume opinionated content, or news sources that other participants perceived as politically biased.

Jump to more on how participants navigate news online.

What topics are considered news?

What the American public considers to be “news” seems to be explained in part by what topic the information falls into.

What is hard and soft news?

These terms are traditionally used in the journalism industry to talk about different types of stories.

Hard news refers to topics that are considered timely, important or consequential for society. This includes stories about politics, the economy and science.

Soft news refers to topics that are often more entertainment-oriented. This includes celebrity, sports, culture and human-interest stories.

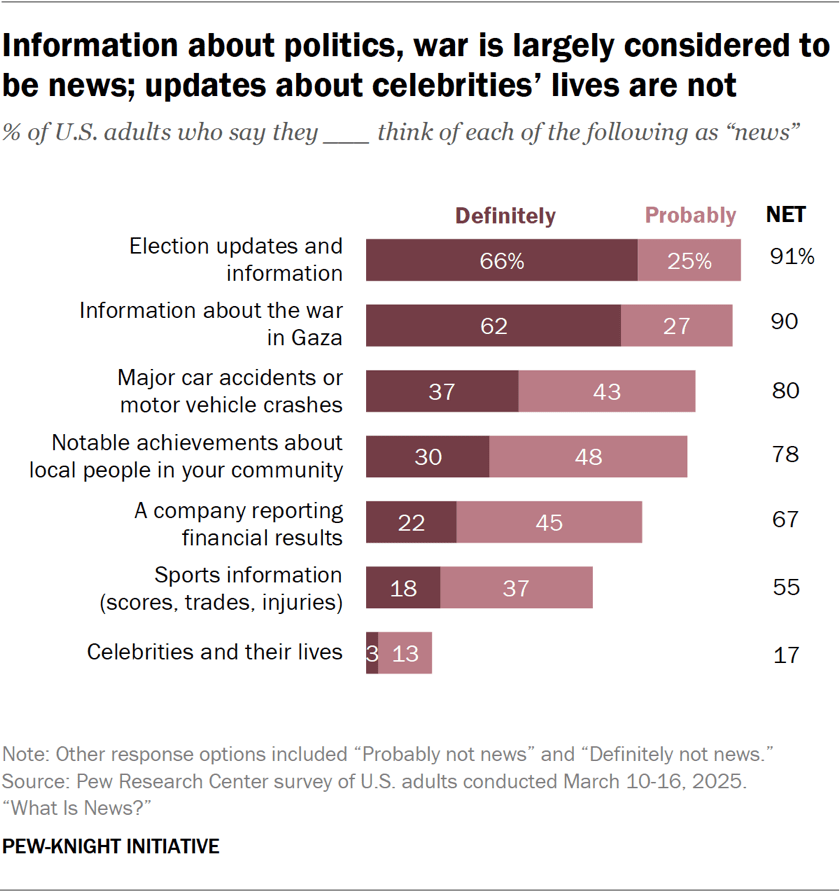

Topics that fit under the journalism industry’s traditional definition of “hard news” – that is, news focused on serious or consequential topics, such as politics, economics, crime and conflict – are more likely to be considered news, often because they are considered more societally important. In both our survey and our online discussion board, people were most likely to consider election updates and information about the war in Gaza to be news. As one man in his 20s explained, “I think if it is serious and impact[s] many people, it is considered news.”

In contrast, topics that could be considered “soft news” – that is, more geared toward providing entertainment – are less likely to be considered news. In particular, people are much less likely to consider information about celebrities to be news than they are any other topic.

As one man in his 30s explained, “I feel like celebrity information or memes are more coverage but not really news specifically. Whereas I associate politics with news and financial information as being news topics.” Put more simply by one woman in her 20s: “Sports and celebrities aren’t news to me. Wars are.”

- Usually considered news: Politics and international conflicts, local crime stories, weather and traffic (particularly instances that were severe or affected more people) were viewed as news.

- Sometimes considered news: Perceptions of sports information were mixed, depending on both the individual participant and the story itself.

- Rarely considered news: Content perceived as “entertainment” – including celebrity stories or topics of personal interest that do not convey “important” information – was rarely seen as news. Neither were videos of animals, lifestyle posts or memes.

The views of our online discussion board participants were echoed in the survey results. Election updates and information about the war in Gaza are considered definitely news by a majority of Americans (66% and 62%, respectively), with about nine-in-ten U.S. adults saying each topic is at least probably news.

For every other topic listed, far fewer Americans said each was definitely news, including major car accidents (37%), notable achievements of people in one’s local community (30%), a company reporting financial results (22%) and sports information (18%). The one item overwhelmingly not considered news was celebrities and their lives, with only 3% of Americans saying they definitely think of this topic as news.

But the topic of information is not the only consideration: The tone or perceived accuracy of news stories overrode these distinctions in some participants’ minds. If the coverage of “hard news” issues was viewed as biased, sensationalized or otherwise inaccurate, it was often less likely to be considered news. One Democratic woman in her 60s shared, “I would not consider misinformation about political issues to be news.” Similarly, according to one Republican woman in her 60s, “Political updates can be news or can be propaganda – depending on the reliability of the source.”

There is another distinction that separates how Americans think of news topics: that of “importance.” For some participants, topics that feel personally important – relevant to them and their community – are more likely to be considered news. This was particularly true for the topic of sports. “I’m sure sports is news to a lot of people, just not me,” one woman in her 60s noted.

One man in his 40s said: “Probably news are not the same thing for everyone. Because, for example, maybe for me that one soccer player scores a goal in a game yesterday is news for me, but probably is not news for someone else that is not interested in soccer at all.”

While these were not always mutually exclusive, other participants centered their own definitions of news around topics of global importance. Among this group, information about elections and international politics is clearly considered news, while local topics may be less likely to be defined as such. As one man in his 20s explained, “Local accidents only affect some people. But [the] Gaza war, elections move the economy.”

What sources are considered news?

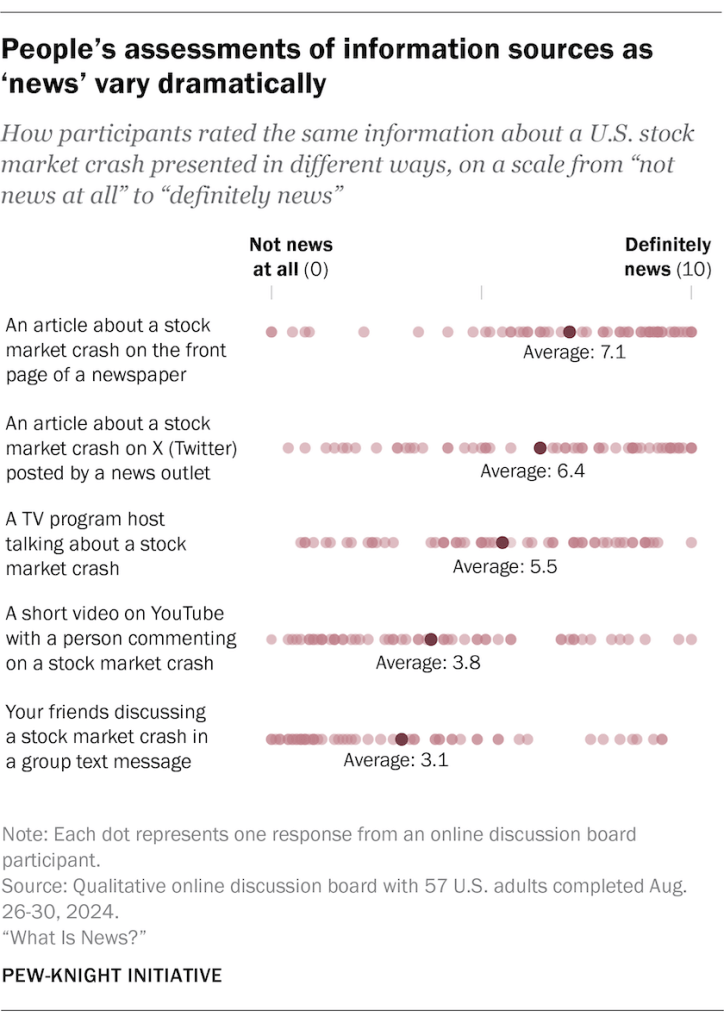

People generally consider a range of information sources and mediums to be “news,” and many assess the same sources very differently. Still, when we asked online discussion board participants to rate information from several types of news sources – including both organizations and individuals – on a scale from “not news at all” to “definitely news,” some patterns emerged. Each scenario focused on a story about “a U.S. stock market crash” to ensure that the main difference in participants’ minds was the source of information and not the topic of that information.

Sources and mediums that specifically mention “news” rise to the top. An article in a newspaper and an article posted by a news outlet on X (formerly known as Twitter) were more commonly seen as news by participants than content coming from a TV program host, a person on YouTube or friends.

However, other qualities, such as the source’s tone or style of delivery, also matter. For instance, some participants interpreted sources “commenting on” or “talking about” the topic as the insertion of opinion, which makes the content less likely to be seen as news.

People also recognize how their ideas about what news sources are, and how they feel about these sources, have shifted over time. Participants noted either sharing or replacing the time they used to spend getting news from print and television, first with websites and then with social media.

One woman in her 30s described her sources of election news changing over the years: “I would watch the news station [to] get my information on TV, but I’ve been getting my information on social media like Twitter over the past couple of years.” One woman in her 40s shared that she used to buy print magazines but has “really adopted fully media on my phone,” adding that they are available digitally now and “traditional news outlets just don’t interest me in the same way anymore because the other social media outlets engage me more.”

“The journey we’re on is 30 years ago, the platforms or places where you could be told something you don’t know aside from being personally told by a friend of yours was very limited. Now, it’s essentially infinite. … The definition of ‘tell me something I don’t know’ is anything, anyone, anytime, anywhere popping up on my phone.”

–Nicholas Johnston, publisher, Axios

Several journalists also reflected on the public’s sources of information changing alongside their understandings of what news is. “The definition of news has changed, and I think the vehicle for consuming news and the news sources have 100% changed,” said Kimi Yoshino, editor-in-chief of The Baltimore Banner.

Social media content was considered by some participants to be less trustworthy – and thus less “news-like” – which aligns with prior Center findings on public trust in information from social media. For instance, participants tended to rate “a short video on YouTube” as less “news-like” than other sources. This also aligned with their actual behaviors when scrolling through their social media feeds.

For instance, one man in his 40s described the content he encounters on X: “So you can see I don’t necessarily take X seriously. It may give me some idea [of], oh, maybe there’s something I want to read more into, but … I don’t see a lot of news here. It’s just a lot of opinions, and obviously, right now it’s very political.”

How identity and trust factor into what sources Americans consider news

A number of our online discussion board participants acknowledged that their personal identities, including their race, ethnicity, gender, religion and political leaning, influence either how they consume or think about news. One woman in her 50s said that her identities “cause me to think and react in certain ways that influence the way that I seek out certain types of news.” Another woman in her 60s said, “I am a Christian with conservative beliefs. I don’t think it affects the way I get the news, but it affects the way I think about the news.”

However, views varied greatly when it came to whether identities should influence how people define or consume news – with some feeling strongly opposed to the concept of identities playing this role. One man in his 70s said, “None of my identities should matter when I consume the news. I do not think identities are at all important. Facts are facts.”

But political identity, whether explicitly stated or implied, was especially relevant for participants. This could stem from either the individual’s own identity or their perception of a source’s political bias – or both.

In some cases, this helped participants make decisions about whether a source counted as news. One Republican man in his 30s said, “I would consider this kind of like semi-news, I guess, because it’s like coming from Fox.” And a Republican man in his 40s dismissed CBS News and MSNBC stories about Trump, saying, “[It’s] the Democrats, that’s not news.”

Even when participants didn’t explicitly feel their identities matter or should matter, some acknowledged that they gravitate toward or are more inclined to choose sources that they feel align with their political affiliations or values.

This mirrors our survey, which found that more than half of Americans (55%) say it’s at least somewhat important for their news sources to have political views similar to their own. Republicans (56%) and Democrats (56%) are equally likely to express this view, while U.S. adults who identify as politically independent or something else and do not lean toward a party (43%) are less likely to see it as important for their news sources to share their political views.

“I think people are just finding it harder to maybe get ‘objective’ information if it completely disregards a personal perspective or value that they have.”

–María Méndez, service and engagement reporter, The Texas Tribune

Trust and politics are important to one another: Our research has found that political affiliations are linked with Americans’ trust in and consumption of news sources. Several right-leaning participants discussed changing news sources they use over time due to no longer trusting them:

“I used to listen to the mainstream media like everybody else, like CNN or MSNBC, but I have found these media outlets no longer supply me with the truthful information that I need.” –Man, 50s, Republican-leaning independent

“I used to get information on politics from Fox News only, but now I try and seek out unbiased sources like Reuters and even more liberal organizations like Apple News and NPR to hear the stories from the other side.” –Man, 20s, Republican

“Political stuff has changed drastically. I no longer view the news that come from sources that are [Democratically] biased and run. These news station[s] only make good comments on Democrats and negative on Republicans.” –Woman, 60s, Republican

What is and isn’t news on social media?

Getting news is not the main reason many users visit social media sites, but people almost universally come across news-related content there. Social media is also a space where the lines between news and other content are especially unclear.

It is a reflection of the changing nature of how news is distributed that audiences can, and regularly do, make distinctions about what kinds of content they are seeing as they scroll through social media. Part of the scrolling experience is making snap judgments about whether content is news and whether to engage with it.

How Americans decide what is ‘news’ when scrolling through social media

Some of the cues Americans rely on when navigating information on their own social media feeds

Source: Do I recognize and trust this name or logo? Is it verified?

Content: Does the headline or post note BREAKING or other cues?

Attribution: Does it provide evidence? Does it have sources or links?

Visuals: Is there a video or on-the- ground footage?

Source: Qualitative online discussion board with 57 U.S. adults completed Aug. 26-30, 2024.

“What Is News?”

PEW-KNIGHT INITIATIVE

How Americans decide what is ‘news’ when scrolling through social media

Some of the cues Americans rely on when navigating information on their own social media feeds

Source: Do I recognize and trust this name or logo? Is it verified?

Headline: Does it note BREAKING or other cues?

Attribution: Does it provide evidence? Does it have sources or links?

Visuals: Is there a video or on-the-ground footage?

Source: Qualitative online discussion board with 57 U.S. adults completed Aug. 26-30, 2024.

“What Is News?”

PEW-KNIGHT INITIATIVE

The online discussion board included a section that asked participants to navigate social media feeds, recording their screens and their own thoughts about what they saw as they did so. When participants scrolled through social media, they drew from similar cues related to both the topic and its source – including that source’s political orientation – to make case-by-case evaluations about whether the information was news or not.

Trust plays a critical role in how people decide whether information they come across is news or not. Our online discussion board participants often decided what they trusted, and therefore what counted as “news” to them, when actually scrolling through their feeds based on a few key factors.

Source familiarity and reputation

Participants typically mentioned trusting established and recognizable news brands and being more likely to consider stories from those sources as news within the context of social media.

Some said they were more inclined to see something in their social media feed as news if they felt it looked like a news outlet. This included posts from “verified” accounts on social media platforms like Facebook and X, as well as those with a clear logo. For example, some participants responded in real time to the sources they encountered on their feeds with comments such as:

“So being posted by ABC News, I would consider that to be news just because it is posted by a news organization.” –Man, 20s

“I would consider this to be news because this is from the CBS itself, and it’s a verified account.” –Woman, 20s

Besides established news organizations, some participants trust individuals as credible news sources because they recognize the poster. When one woman in her 60s looked at a post about local traffic updates by a fellow member of a community Facebook group, she felt it was “definitely news” because the person who shared the update frequently posted this type of content. “He’s legit,” she said.

When we asked participants to scroll through the social media site they use the most, it was not uncommon to see participants selecting online groups that post local updates, such as on Facebook. According to a 2024 Pew Research Center study, online forums or groups have become increasingly popular among Americans as a source for local news and information.

Visuals, evidence and depth

Bold headlines and terms like “BREAKING” tended to make participants more likely to consider posts in their social media feeds as news.

Additionally, participants often expressed interest in, or at least paid more attention to, content that included images or videos. Seeing something with one’s own eyes, such as content presenting documented evidence or linking to sources, seems to make it feel more “news-like.” “Eyewitness” or on-the-ground footage is seen as more trustworthy, though several participants noted rising concerns around AI making it harder for them to trust what they see.

Participants also placed value on perceived quality or depth in assessing whether a post was news. For example, clips of public figures or politicians’ statements from news outlets didn’t necessarily count as news for some participants because they “didn’t get the full context” or “it wasn’t novel information.”

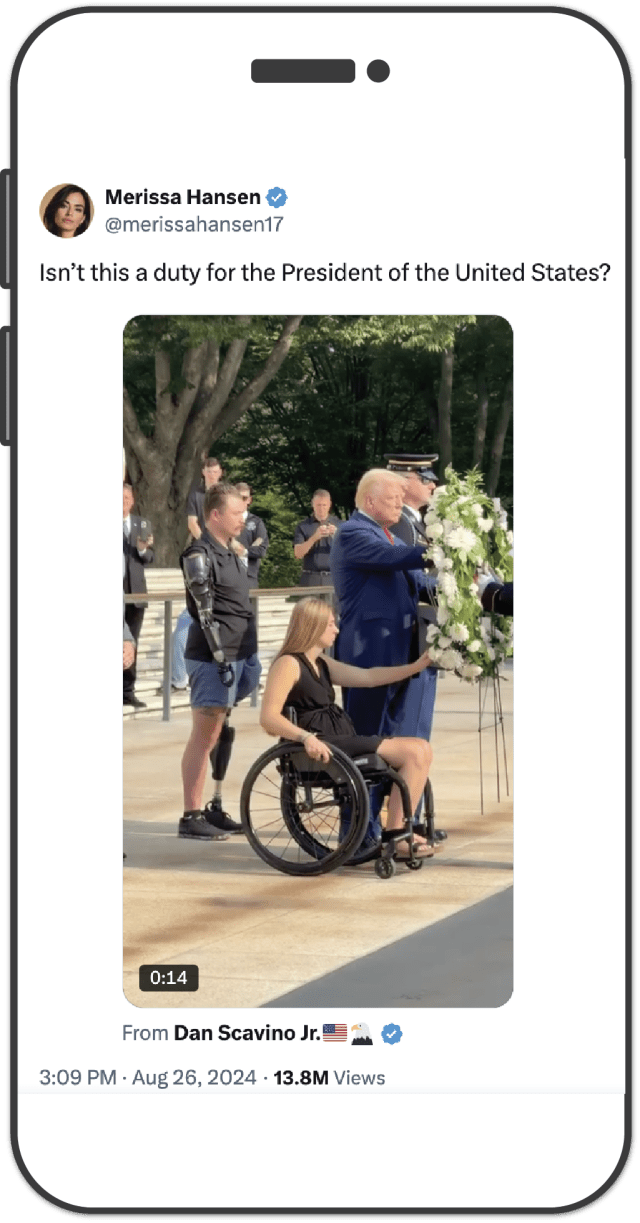

Is this news?

Here are some of the posts participants encountered in this activity. Click to find out whether they said each is news.

One woman in her 30s thinks a TikTok post about the Russia-Ukraine war IS news because it comes from CBS, which she sees as a news source.

One woman in her 60s thinks a Facebook group post about local traffic IS news because the poster is a “legit” source who frequently posts about traffic accidents.

One woman in her 40s thinks a clip of Donald Trump at an event IS NOT news “in and of itself,” though she thinks “it could be made into a news story.”

One woman in her 30s thinks a TikTok post about the Russia-Ukraine war IS news because it comes from CBS, which she sees as a news source.

One woman in her 60s thinks a Facebook group post about local traffic IS news because the poster is a “legit” source who frequently posts about traffic accidents.

One woman in her 40s thinks a clip of Donald Trump at an event IS NOT news “in and of itself,” though she thinks “it could be made into a news story.”

One woman in her 30s thinks a TikTok post about the Russia-Ukraine war IS news because it comes from CBS, which she sees as a news source.

One woman in her 60s thinks a Facebook group post about local traffic IS news because the poster is a “legit” source who frequently posts about traffic accidents.

One woman in her 40s thinks a clip of Donald Trump at an event IS NOT news “in and of itself,” though she thinks “it could be made into a news story.”

Navigating personalized online news experiences

As Americans increasingly rely on digital channels, including social media, to get their news, exposure to content curated by algorithms based on user interests and interactions has become an everyday part of the news experience.

“I think tech has made how you get your news and what that news is very personalized, but for better or for worse, via algorithms or not, if you are actively pursuing information, it’s gotten a lot more customizable – both as a consumer, as a reader, as a listener, as a viewer, but also on the news front as well.”

–Julia B. Chan, editor-in-chief, The 19th

Our online discussion board participants were aware that algorithmic curation takes a variety of formats, such as within “Trending,” “Discover” or “For You” pages on social media sites and aggregators. Some participants purposely check for trending content that informs people about what is happening and is likely to cater to their individual interests.

For example, one man in his 30s discussed enjoying Google’s Discover feed, saying, “It just gives me what I’m interested in. The algorithm really knows me. And for some reason, everything here is of my interest. I’m impressed.”

Meanwhile, some participants expressed confusion about recommended content that they didn’t actively choose to follow. One man in his 40s said, “What you’re going to see on X for me is a lot of political stuff, and I don’t know where it’s coming from. I must have responded to stuff that, all of a sudden, links me to it. So my algorithm must be there.”

The journalists we interviewed also recognized audience shifts toward personalized experiences and shared how this has changed their processes for determining what “news” is and which stories to cover.

For them, the personalization of news has a big impact: News curation and editorial decisions are no longer confined to the newsroom. “We can tell just what people are clicking on,” said Matt Collette, a former editor of Vox’s daily news podcast Today, Explained. “That’s really a blunt instrument, but it can tell us, people seem to be really interested in this topic right now.”

“You can search for whatever you want. You can search for what you’re interested in. That makes everyone like a wire service editor. That’s good. That’s also bad because they’re not trained to be the best wire service editor.”

–Tracy Weber, managing editor, ProPublica

A few journalists we interviewed mentioned the process of news curation being based more on virality nowadays than on journalists’ experience or ideas of what might be societally important. “Sometimes maybe what constitutes news now is what people find interesting rather than necessarily what’s in the public interest,” said Rebecca Hutson, editor-in-chief of The News Movement. “Sometimes the output of news organizations can be governed a lot by where traffic and interest lies.”

Jeffrey Goldberg, editor-in-chief of The Atlantic, said, “The reason you have editors is because editors presumably know how to find and tell stories that are both of interest to their readers and also have some larger social good involved with publishing those stories.”

How Americans feel about news

People have mixed emotional responses to news. While many of our online discussion board participants portrayed it negatively – usually citing the mental burden brought by news about politics, crime and war – they also showed both positive and negative feelings when we asked them to use images to illustrate how they feel about news. “I need to know what is going on in the world, no matter how upsetting,” one man in his 70s said.

In our survey, we asked U.S. adults to indicate how often the news they get makes them feel each of several emotions. Of the emotions they were asked about, Americans generally say they feel negative ones more often than positive ones.

The one exception to this pattern involves feeling informed. Nearly half of Americans (46%) indicate the news they get makes them feel informed extremely often or often, and the vast majority of Americans (89%) say it makes them feel this way at least sometimes.

But the next four most commonly felt emotions are all negative ones. Roughly four-in-ten Americans say the news they get makes them feel angry or sad at least often (42% and 38%, respectively). And about a quarter say it at least often makes them feel scared (27%) or confused (25%).

Smaller shares say the news they get makes them feel hopeful (10%), happy (7%) or empowered (7%) extremely often or often.

How news makes this participant feel

Click to view the images the

participant chose

“I am trying to show my conflict between enjoying being informed, and feeling like I NEED to be informed, and my often disgust with what I read. Sometimes the really horrible stuff leaves me quite depressed for a while.”

–Woman, 60s

How news makes this participant feel

Click to view the images the

participant chose

“I am trying to show my conflict between enjoying being informed, and feeling like I NEED to be informed, and my often disgust with what I read. Sometimes the really horrible stuff leaves me quite depressed for a while.”

–Woman, 60s

Online discussion board participants were asked to construct a collage of images and text that portrayed how they felt about the news. These images revealed people’s mixed feelings when thinking about news. Participants noted feeling conflicted between desiring to be informed – or even feeling a need to be informed – and feeling sad, angry or overwhelmed by the information they come across.

Negative feelings toward news

Some participants noted that their negative feelings about the news are due to common topics of coverage, such as politics, crime and war. One woman in her 40s said, “Stories I react negatively to include stories about crime, mass shootings, war, political name-calling, people behaving badly, people dying, animals dying, etc.”

Some said these types of news make them feel sad and have a negative outlook on the state of their community, the country or the world. For instance, one woman in her 50s felt that “reading the news on the Ukrainian war makes me feel sad and discouraged.” One woman in her 30s said, “I react negatively to political news because our nation is so divided.”

Others indicated that their negative feelings originate from feeling overwhelmed by either the quantity or content of news, particularly online. “At times when there are big things happening, I seek out the news,” one woman in her 60s said. “I can become overwhelmed however and need to step away for a while.” Another woman in her 60s, when illustrating her feelings about news, added a text box that simply said, “Sometimes I feel confused.”

“The consumers who felt like 20 years ago we were stuck with this very limited amount of information, now feel overwhelmed by there being too much information.”

–Ben Smith, editor-in-chief, Semafor

V Spehar, an independent journalist and creator of Under the Desk News, said, “To constantly just flood people with information and constant breaking news updates, it exhausts them.”

Some participants explained that these feelings resulted in them actively avoiding news, at least occasionally. “I think I’m in the middle when it comes to [actively seeking out or avoiding news],” one man in his 40s said. “I like to stay informed, but I think sometimes too much information can cause an overload.”

People’s negative emotions were also at times connected to a general distrust of news or the news media broadly, or to perceptions of political bias. “It’s unknown whether anything we’re told is true,” one woman in her 40s said. “I think I have a real distrust right now. … I think the truth is being hidden from us.” One man in his 50s explained, “I am negative towards election news, it is so biased depending on the nominees, more like cheerleading.”

Finally, in some cases, participants’ partisan identities or political leanings spurred their negative emotional reactions toward news. Our qualitative research took place ahead of the 2024 U.S. presidential election, and some participants specifically mentioned their dislike of news covering either Donald Trump or Kamala Harris, depending on their political affiliation.

“Honestly, I automatically hate stories trying to show Trump in a positive light,” one Democratic man in his 40s said. Meanwhile, one Republican woman in her 20s explained, “I also don’t like to hear anything about the presidential candidate Kamala Harris or I don’t like to hear anything about the current president Joe Biden, it’s always annoying or irritating.”

These examples made it clear that for some, emotions about news can be tied to particular moments in time, and those feelings can change alongside shifts in political power. “It seems that any news stories about the current [Biden] administration I will react negatively to because I don’t really care for them,” one Republican-leaning independent man in his 50s said in the lead-up to the 2024 election.

Our March 2025 survey data further illustrates this point. After the change in administrations, Democrats and independents who lean toward the Democratic Party are substantially more likely than Republicans and Republican leaners to say the news they get makes them feel angry (53% vs. 32%, respectively), sad (50% vs. 27%) or scared (39% vs. 15%) extremely often or often.

Positive feelings toward news

At the same time, large shares of Democrats (51%) and Republicans (42%) say the news they get makes them feel informed at least often. And 14% of Republicans say it makes them feel hopeful, compared with 5% of Democrats.

Some online discussion board participants had positive emotional reactions to news, particularly when it discussed certain 2024 presidential candidates:

“When Kamala was announced to be running for the presidential debate, I [had] a strong positive reaction to this, it made me feel interested and somewhat excited.” –Woman, 20s, Republican-leaning independent

“I do like to check up and see what Trump is doing. I find him very interesting.” –Woman, 20s, Republican

Although many participants depicted or described negative feelings toward news in their canvas illustrations, they also drew upon positive emotions and images, ranging from smiling faces and lightbulbs to depictions of human connection or progress. At times, these appeared to serve as a counterbalance to their negative emotions, with participants portraying both side-by-side to depict their contrasting feelings about news.

Aligning with our survey findings, being informed was mentioned by many participants as both an important factor in why they consume news and a feeling they experience from doing so. Some mentioned being informed as a reason they enjoy consuming news. Others said they balance feeling obligated to stay informed about news with knowing it would ultimately make them feel bad.

What do people want from their news?

Ultimately, what people want from the news they consume is more complicated than it appears. When we asked online discussion board participants what one thing they would change about the way news is currently presented, some said they want news to be:

“Watching the news just became really stressful for people, and think about what people have going on in their lives outside of interfacing with us. What product are you going to spend time with or engaging in that makes you feel like s–t or stresses you out?”

–Sean McLaughlin, vice president of news, Graham Media Group

- “Just the facts.” In our qualitative research, people generally said they want information without opinions or commentary. However, participants’ actual behaviors at times contradicted this preference, and in our March survey, a majority of Americans still say it’s important that their news sources have political views similar to their own.

- More positive. “I would change how negative stories are just presented with no warning,” one woman in her 20s said. “Sometimes I don’t want to know about that. I wish they had an option for only positive news stories.” Several participants said they enjoy human-interest stories because they are often more positive and less opinion-driven. At times, this desire for positivity can conflict with people’s ideas of topics such as politics, war and crime as being more news-like – and their perceptions of those very topics as inducing negative emotions – as well as with the overwhelming perception that “entertainment” is not news.

- Transparent, both among news institutions and in news coverage. For a few participants, this included sharing information at the organizational level, such as ownership structure or political donations, as well as at the individual level, such as sources’ or journalists’ biases and interests.

These include some vexing contradictions that mirror the messiness of the modern information environment. But they also reflect people’s enduring and shared desire to get a clear and unvarnished – and, if possible, uplifting – perspective on the world around them.

About this essay

This is a Pew Research Center analysis from the Pew-Knight Initiative, a research program funded jointly by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

This was a collaborative effort based on the inputs and analysis of a number of people at Pew Research Center. We are thankful for the work of former Pew Research Center senior writer Mark Jurkowitz, who conducted this study’s interviews with journalists and editors, and the PSB Insights team, who conducted the online discussion board. Finally, this project was guided by an advisory board who provided invaluable feedback at several stages throughout this project: Matt Carlson, Stephanie Edgerly, Rachel R. Mourão and Jacob Nelson.

Collage images are from Getty Images.